By Olga Kwasnicka, MA student in Sustainable Heritage Management, Aarhus University, 2019-2021

Every year, over the course of a semester, Sustainable Heritage Management students at Aarhus University in Denmark complete a module on Heritage Project Management which focuses on working with “real world” heritage issues. One group in 2019 worked to develop a project proposal for the future use of Sean McDermott Street Magdalene laundry. In developing an understanding of the site, the team relied extensively on the work of advocacy groups such as Justice For Magdalenes (JFM) (now Justice For Magdalenes Research), whose concerns influenced the team’s decision to frame the project in terms of transitional justice. Transitional justice’s privileging of the voices of marginalised communities resonates with developments in heritage and museology that seek to disrupt official historical narratives, and find socially responsible ways of making heritage. It is now generally accepted that a socially responsible museum is one that continually asks itself: What stories are important to share? How are they to be told? To what end? Increasingly, community collaboration and an explicit social justice imperative are used as frameworks for answering these questions, as they have been in these students’ project.

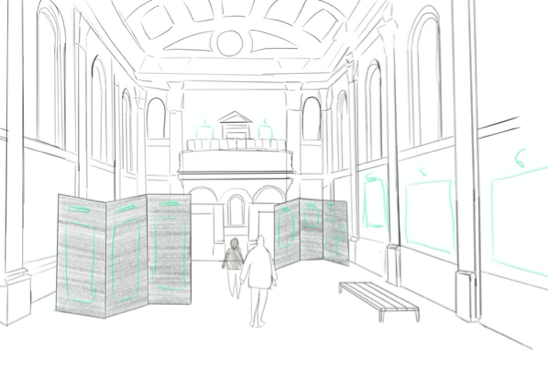

After undertaking detailed research into the history of the Magdalene laundries and their relationship with Irish society, the students proposed that the buildings that remain on the site could be used to create “a site of active remembrance.” This would consist of an historical exhibition located in the women’s dormitories, and a community performance space in the de-consecrated church. The other remaining building – the convent – was not included in their intervention. These spaces were chosen to “resist and counteract the shame that has historically been forced upon Irish women” and the silence that those working in the laundries were bound to. By focusing on the architecturally mundane but socially important women’s dormitories, the project placed their voices centre-stage. Although broader narratives – like nationalism or State-Church relations – could be explored to provide context and to enable critical engagement with the systemic nature of the abuse, it was clear to the students that their main goal was to ensure that the structures were used to narrate the women’s own stories, and to “ensure their visibility throughout the entire site”. Throughout the exhibition women’s voices would literally be heard through various sound installations – this would include using oral testimonies gathered by Justice for Magdalenes Research to be played in the dormitory – and their presence evoked through the display of personal belongings and everyday objects like a nightstand or a bed.

These choices reflect a desire by the students to create opportunities for personal and emotional connections between the audience and those whose stories are being told. A proposed museumization of the former Magdalene Laundry buildings at Sean MacDermott street is perhaps uniquely positioned to do so. The remaining buildings have the potential to evoke powerful emotions and encourage empathy among visitors. However, care has to be taken in using the site, as how we interpret it affects which stories we are capable of telling. In this regard, the students were careful not to overemphasize the church and not to leave its aesthetic appeal unfiltered. They argued that traditional power dynamics must not be reinforced and the site must move beyond an old-fashioned understanding of heritage as the monumental or aesthetically pleasing. They suggested rather that all religious objects be removed from the church and the building be converted to a community space.

Design sketch of chapel. © Lea Pedersen

Part of the students’ intended outcome was to make clear to the audience that they were not being presented with the Magdalene laundries as part of a long gone, distant past. Connecting the site to the present was also important and took two main forms. Firstly, the team planned for the historical exhibition to be concluded with an “after the laundry” room, which focused on the work of survivors and representative organisations in obtaining justice and the elements that were still being campaigned for. Secondly, the students proposed that the Church be converted into a gallery and performance space. Inspired by the concept of a site of conscience – a historic space that drives public debate on contemporary issues (Sevcenko 2010) – they envisaged this as “a space of community conscience that will be used to address contemporary issues surrounding social injustice in Ireland.” The team recognised that active involvement and the inclusion of community-focused roles would be key to the sustainability of the site. In particular, if the site is to function as a site of conscience then it is imperative that the perspectives it offers be continually reassessed, and brought to bear on emerging issues.

As a student of heritage management myself, I recognise the difficulties these students encountered in addressing what some might call “dark heritage”. Dark heritage is a term associated with historical places or events that perturb the public consciousness (Stone 2013). Often these are sites of death, conflict or atrocity which in being made public as heritage reveal what would more comfortably be hidden. Dark heritage is therefore almost always “difficult heritage” (MacDonald 2010) that produces tension over interpretation and the right to display. In the case of memorialising the Magdalene Laundries, while one wants to convey women’s experiences of oppression and exploitation, it is at the same time important to avoid sensationalising the site by making it only about stories of abuse. Apart from being insensitive, such an approach would do an injustice to the women survivors, whose stories are also about strength and dignity, and in many cases resistance and resilience. Whatever the final form of the Sean MacDermott street site, we have a unique opportunity of creating a history of the laundries from the perspectives of those working in them, correcting years of popular prejudice, denial, and skewing the realities of these institutions by both the church and state. The challenges moving forward from a heritage perspective will be to ensure the retention of materials associated with the site and their use in creating a plural yet coherent narrative that can continue evolving, while retaining the centrality of survivors’ experiences moving forward. There is a need to consider how to make the most of the physical site and to push ourselves, as heritage managers, to be critical, asking questions about what our responsibilities are to the past as well as to the present.

Bibliography

Macdonald, Sharon. 2009. Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi Past in Nuremberg and Beyond. London; Routledge.

Stone, Philip. Dark Tourism: a critical review. Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research. 7(3): 307-318

Sevcenko, Liz. 2010. Sites of conscience: new approaches to conflicted memory. Museum International. 62(1-2), 20-25.