This page was created by Kelly Ledoux, Attorney and LLM candidate at the Irish Centre for Human Rights, NUI Galway, 2019-20.

People who were detained in Magdalene Laundries, Mother and Baby Homes, County Homes, Industrial and Reformatory Schools and other related institutions in 20th century Ireland, and those forcibly separated from family members through the adoption system, were grossly and systemically abused for decades while society turned a blind eye and the State in many ways participated. Many other systematic institutional and gender-based practices, including symphysiotomy and the treatment of people detained in psychiatric institutions, also form part of this legacy of abuse.

Even though the institutions are now closed, Ireland has a legal duty under international human rights law, European human rights law and arguably also Irish Constitutional law to provide survivors and the family members of those who have died with memorialisation as an important form of remedy for the past violations they suffered. (Many other forms of remedy are also required.)

Human Rights Law

International human rights law and European human rights law require states to provide redress and reparations to victims of human rights violations. Similarly, the Irish Supreme Court has held that there is a right to a remedy for breaches of Constitutional rights.

Ireland’s institutional and adoption-related abuses during the 20th century clearly violated numerous provisions of human rights treaties to which Ireland is a party, including the following:

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination of Women

- International Labour Organization Forced Labour Convention

- International Labour Organization Abolition of Forced Labour Convention

- European Convention on Human Rights

Numerous international, European and Irish human rights bodies and experts have agreed that the publicly available evidence of what happened to children and women in Industrial and Reformatory Schools, Magdalene Laundries, Mother and Baby Homes, County Homes and similar institutions, and through the forced adoption system and symphysiotomy, during the 20th century in Ireland points to serious and systematic violations of human rights.

These bodies include the UN Committee against Torture in 2011 and 2017, the UN Human Rights Committee in 2014, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2015, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women in 2017, and the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 2019. The international experts include the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights in 2017, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the sale and sexual exploitation of children in 2019.

In 2013, the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission published a report stating that the Magdalene Laundries “operated as a discriminatory regime”, that “women were deprived of their liberty [and] the lawfulness of such detention is questionable in a number of respects”, and that “the State’s culpability in regard to forced or compulsory labour and/or servitude appears to be threefold.”

Organisations such as Justice for Magdalenes Research, Adoption Rights Alliance, the Clann Project, Amnesty International, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties and the National Women’s Council of Ireland have also explained in their public reports the gross and systematic human rights violations that occurred.

Redress and Reparations Under International Human Rights Law

According to numerous international human rights law instruments, “redress” for gross and systematic human rights violations involves numerous elements, including but going far beyond criminal investigations and prosecutions and access to the civil courts.

For example, the UN Committee against Torture has made clear redress for torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment must include (1) restitution, (2) compensation, (3) rehabilitation, (4) satisfaction and (5) guarantees of non-recurrence. Measures of “satisfaction” by the state could include:

- Verification of the facts and full and public disclosure of the truth;

- An official declaration or judicial decision restoring the dignity, the reputation and the rights of the victim and of persons closely connected with the victim;

- Judicial and administrative sanctions against persons liable for the violations;

- Public apologies, including acknowledgment of the facts and acceptance of responsibility; and

- Commemorations and tributes to victims.

The UN General Assembly’s Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law lays out three elements of the right to a remedy:

- equal and effective access to justice,

- adequate, effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered, and

- access to relevant information concerning violations and reparation mechanisms.

The second aspect of reparation specifically includes “verification of the facts and full public disclosure of the truth; commemorations and tributes to the victims; and inclusion of an accurate account of the violations that occurred…in educational materials at all levels.”

Over the past decade, several UN human rights treaty bodies have issued formal recommendations to Ireland regarding the abuses committed in Magdalene Laundries, Mother and Baby Homes and County Homes, Industrial and Reformatory Schools and other related institutions, and through forced adoption and the practice of symphysiotomy. These recommendations have included:

For further information, please find links below to the various bodies’ concluding observations and reports:

- UN Committee against Torture in 2011 and 2017;

- Human Rights Committee in 2014;

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2015;

- Committee on Elimination of Discrimination against Women in 2017;

- UN Special Rapporteur on sale and sexual exploitation of children in 2019; and the

- Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights in 2017.

Transitional Justice

The United Nations has defined transitional justice as “the full range of processes and mechanisms associated with a society’s attempt to come to terms with a legacy of large-scale past abuses, in order to ensure accountability, serve justice and achieve reconciliation.”

While transitional justice typically addresses “how societies reckon with a legacy of gross violations of human rights in the context of a transition from armed conflict or authoritarian rule to stable, peaceful liberal democracy,” the approach has recently begun to be utilised in remedying historical abuses regardless of whether conflict or authoritarian regimes (as typically understood) were involved.[1] In November 2018, Dr James M Smith, Dr Katherine O’Donnell and Dr Maeve O’Rourke convened an international conference at Boston College to consider the extent to which the framework of transitional justice might assist Ireland to meet its obligations towards those who suffered in Ireland’s network of institutions and gender-based abuses during the 20th century.

According to the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), the goals of transitional justice always include “the recognition of the dignity of individuals, the redress and acknowledgment of violations, and the aim to prevent them from happening again.” There are typically four elements or approaches to transitional justice:

- truth-seeking,

- prosecutions,

- reparation, and

- reform.

These four elements of transitional justice are similar to the definition of redress under the international human rights law instruments outlined above.

The Right to Truth Provided By Transitional Justice Mechanisms

The Updated Set of Principles for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights Through Action to Combat Impunity, or also known as the Joinet/Orentlicher Principles, set out the following rights regarding the right to truth and preservation of memory:

PRINCIPLE 2. THE INALIENABLE RIGHT TO THE TRUTH

Every person has the inalienable right to know the truth about past events concerning the perpetration of heinous crimes and about the circumstances and reasons that led, through massive or systematic violations, the perpetrations of those crimes. Full and effective exercise of the right to the truth provides a vital safeguard against the recurrence of violations.

PRINCIPLE 3. THE DUTY TO PRESERVE MEMORY

A people’s knowledge of the history of its oppression is part of its heritage and, as such, must be ensured by appropriate measures in fulfilment of the State’s duty to preserve archives and other evidence concerning violations of human rights and humanitarian law and to facilitate knowledge of those violations. Such measures shall be aimed at preserving the collective memory from extinction and, in particular, at guarding against the development of revisionist and negationist arguments.

PRINCIPLE 4. THE VICTIMS’ RIGHT TO KNOW

Irrespective of any legal proceedings, victims and their families have the imprescriptible right to know the truth about the circumstances in which violations took place and, in the event of death or disappearance, the victims’ fate.

In 2017, the Irish Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, Katherine Zappone, made an announcement that she was seeking a “transitional justice approach to provide remedies for victims of institutional abuse.”

Several survivor consultations and official reports in Ireland have recommended memorialisation of various forms however the Government has not responded to these recommendations in a systematic or nation-wide manner to date.

A submission in January 2020 by Dr Maeve O’Rourke to the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence explains the measures that some individuals and institutions have taken to ensure that the memory of Ireland’s legacy of abuse is preserved. The submission also highlights the State’s failures in this regard, and the need for the State to meet its human rights obligations by ensuring national education and other forms of memorialisation in order to respect the dignity of victims and survivors and prevent similar abuse from recurring.

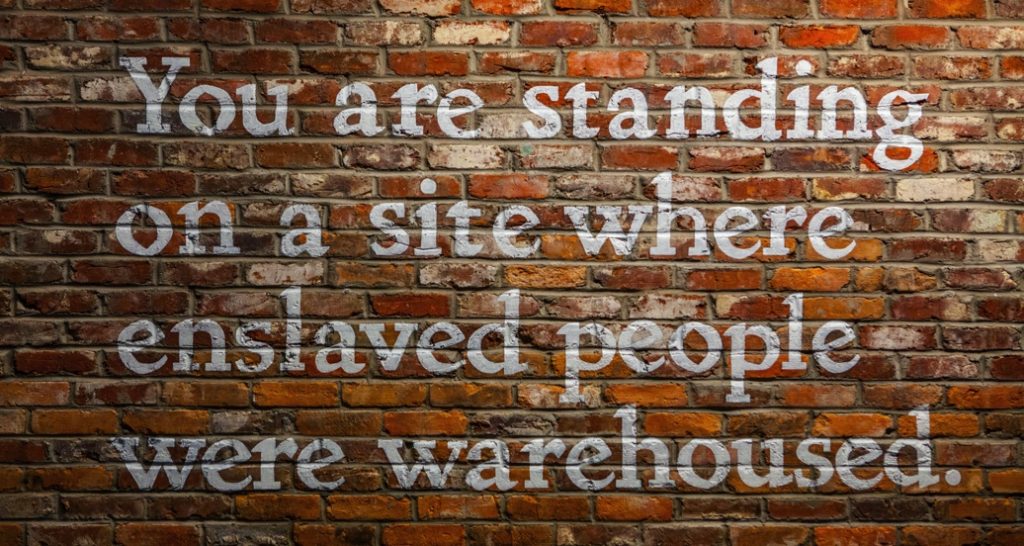

Memorialisation and Sites of Conscience

Memorialisation is an important part of transitional justice and redress for gross and systematic human rights violations. It is generally defined in the dictionary as the process of creating public memorials such as museums, monuments and sites of conscience. Sites of conscience have been described by the ICTJ as “public memorials that make a specific commitment to democratic engagement through programs that stimulate dialogue on pressing social issues today and that provide opportunities for public involvement in those issues.”

As discussed above, the State has a duty to provide redress to victims which includes public disclosure of the truth, commemorations and tributes to victims, and an accurate account of events in educational materials at all levels. Thus, the State has an obligation to memorialise but there is no clear cut requirement of what that looks like. As there are many legal instruments governing remedies and redress of human rights abuses, there are also numerous perspectives on memorialisation as discussed in a report based on an international conference “Memorialization and Democracy: State Policy and Civil Action“:

There can be no single blueprint for public memorials, nor a recipe for what they should be or what they should look like. On the contrary, the worst thing we can do is to imitate models or try to export them. This would threaten the two most necessary components of creating public memory sites – context and creativity.

The ICTJ provides examples of several types of memorials or sites of conscience but this list is by no means exhaustive:

- “living” memorials such as community centers, markets and peace gardens;

- dedicating commemorative monuments, plaques, statues, stupas, or other memorials to victims;

- erecting tombstones or building new cemeteries;

- renaming streets, buildings, and public spaces;

- developing educational or health care facilities;

- building museums or public parks;

- creating public art or conceptual art projects;

- designating national days of remembrance;

- conducting celebrations that offer atonement and promote reconciliation;

- rededicating places of detention and torture, prisons and military facilities;

- marking and honoring mass graves;

- organizing mobile museums or traveling instillations, including photo, film, and video presentations or exhibits; and

- naming legislation in honor of victims.

While memorials can bring together and encourage reconciliation, the process of creating a memorial can become highly politicalised and create divisions among communities, victims, activists, stakeholders, and the government. These divisions could potentially cause so much delay that no memorial or site of conscience is ever built. But if memorialisation is rushed, there is a risk victims are not adequately consulted and included in the process. Regardless of what the memorial site looks like or when it is built, “memorials or the preservation of memory sites should never be at the expense of truth and justice” and “memorials should be about remembering, not forgetting: connecting past, present and future.”[2]

The International Coalition of Sites of Conscience is a worldwide network for sites of conscience with over 275 members in 65 countries. This Coalition helps build memorialisation programs and connect members who are experts in the field of human rights, transitional justice, arts and culture, and musicology. There are currently no Coalition member sites in Ireland – Sean McDermott Street would be the first. Some international Coalition members include:

It is important to note that it is not necessary for a memorial or site of conscience to join the Coalition to still be considered as a site of conscience. Please see additional international examples from around the world:

The Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice

[1] James Gallen, “The European Court of Human Rights, Transitional Justice and Historical Abuse in Consolidated Democracies,” Human Rights Law Review 19, 4 (2019): 677; see also James Gallen, “Jesus Wept: The Roman Catholic Church, Child Sexual Abuse and Transitional Justice,” International Journal of Transitional Justice 10, 2 (2016): 332-49.

[2] Sebastian Brett, Louis Bickford, Liz Ševčenko, and Marcelo Rios, “Memorialization and Democracy: State Policy and Civil Action” (International conference, Santiago, June 2007): 27 https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-Global-Memorialization-Democracy-2007-English_0.pdf.