History of Magdalene Institutions in 20th Century Ireland

There were ten Magdalene Institutions in twentieth-century Ireland and in contrast to their nineteenth- century forebears they were carceral Institutions, no longer providing shelter to women who were free to come and go according to their need for respite from a life lived on the streets. The twentieth-century Irish Magdalenes were punitive Institutions where socio-economically vulnerable girls and women were held under lock and key and forced into unpaid hard labour at laundry or needlework. The rationale for the incarceration was religious: girls of the Magdalene were frequently victims of rape and incest, and other girls and women were regarded as being guilty of or vulnerable to being sexually active outside the bonds of marriage. The Magdalene Institution was designed so that the girls and women confined there could do penance to atone for the sexual sins that they were adjudged to have committed or be in danger of committing.

The wide range of human rights violations that girls and women suffered in Magdalene Laundries has been recognised by Irish and international human rights bodies, as noted in this report by Dr Maeve O’Rourke and Justice for Magdalenes Research to the United Nations Committee Against Torture in 2017. The Magdalene Oral History Project led by Associate Professor Katherine O’Donnell at University College Dublin provides access to testimonies of many survivors and other people with experience of the Magdalene Laundries. Further sources of testimony are listed on our ‘Further Information’ webpage, here.

Survivor testimony portrays a system in which girls and women were: involuntarily detained in behind locked doors and high walls, with no information as to whether or when they would be released and subject to the threat of arrest by An Garda Síochána (the Irish police force) if they escaped; stripped of their identities, including through the imposition of house names and/or numbers, uniforms, haircuts and a prohibition on speaking; banned from communicating with the outside world except under strict surveillance; verbally denigrated and humiliated; kept in cold conditions with minimal nourishment and hygiene facilities; denied any education; and forced to work, constantly and unpaid, at laundry, needlework and general chores through the coercive force of the above factors and additional punishments including deprivation of meals, solitary confinement, physical abuse and humiliation rituals.

In February 2013, Taoiseach Enda Kenny issued a State Apology to the former inmates of the Magdalene Institutions. A Redress and Restorative Justice Scheme was established in May 2013. Over 800 Survivors have come forward to participate in the Scheme. For more information, please visit Justice for Magdalenes Research.

Related Institutions and Family Separation Practices in 20th Century Ireland

With a heavy accent on ensuring social purity and sexual respectability, the Irish Republic maintained a system of incarcerating vulnerable women and children for most of the twentieth-century. Ireland did so by using the largely-inherited British colonial system of massive Victorian institutions run by Catholic religious orders which had provided basic levels of relief to the Irish poor.

Most of these institutions were established after wide-scale famine in the 1840’s had devastated the population and as starvation and poverty continued to be endemic in the decades thereafter. The Irish middle class (and those aspiring to gain social respectability for their families) joined religious life in great numbers in the later decades of the nineteenth century, a pattern that continued until the later decades of the twentieth century.

The colonial Victorian apparatus of mass institutionalisation of the socially and economically vulnerable (particularly women and children) was maintained by a system of capitation-payments to the religious orders from the Irish State exchequer for most of the twentieth century. The Irish establishment of Church and State also built Mother and Baby homes and some purpose-built Industrial schools.

Ireland’s prison population was a relatively negligible percentage of the population at this time (there was an average of just 50 women held in Irish prisons), yet by 1951, as scholars Ian O’Donnell and Eoin Sullivan have demonstrated, about one in every hundred Irish citizens was incarcerated in an institution operated collaboratively by the Church/State establishment which included psychiatric hospitals, industrial schools, residential schools for disabled children, Mother and Baby homes and Magdalene Institutions.This coercive confinement is referred to by scholars as Ireland’s architecture of containment and we can see that its policing had a gender, class, ethnic and disability focus that upheld patriarchal, married, middle class, white, settled and able-bodied norms.

The architecture of containment was concentrated on the surveillance and monitoring of all women, and where considered necessary, the incarceration of poorer women and their children as well as Travellers and so-called ‘illegitimate’ Irish children (particularly those designated as ‘mixed race’) and the institutionalisation of children and adults with disabilities. Legacy issues of this system of surveillance, punishment and incarceration are still manifest in twenty-first century Ireland: one prime example being that adopted people are denied their rights to their birth certs and adoption files, and other examples being the continuing over-institutionalisation (with capitation payments from the State to commercial enterprises providing institutional care) of older people, people with disabilities and people seeking asylum.

‘The Magdalenes’ (TrueTube, 2014).

In this film, produced for TrueTube by Nick Carew as a teaching aid for secondary school students, Gabrielle O’Gorman revisits the Sean McDermott Street Magdalene Laundry site where she was held prisoner as a teenager. The film was made by Nick Carew, funded by the University of Kent and completed with the help of Associate Professor Katherine O’Donnell at University College Dublin and Professor Gordon Lynch at the University of Kent.

The Magdalene Laundry at Sean McDermott Street, Dublin 1

Chapter 3 of the Government’s “Report of the Inter-departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalene Laundries”, published in 2013, explains the history of the site:

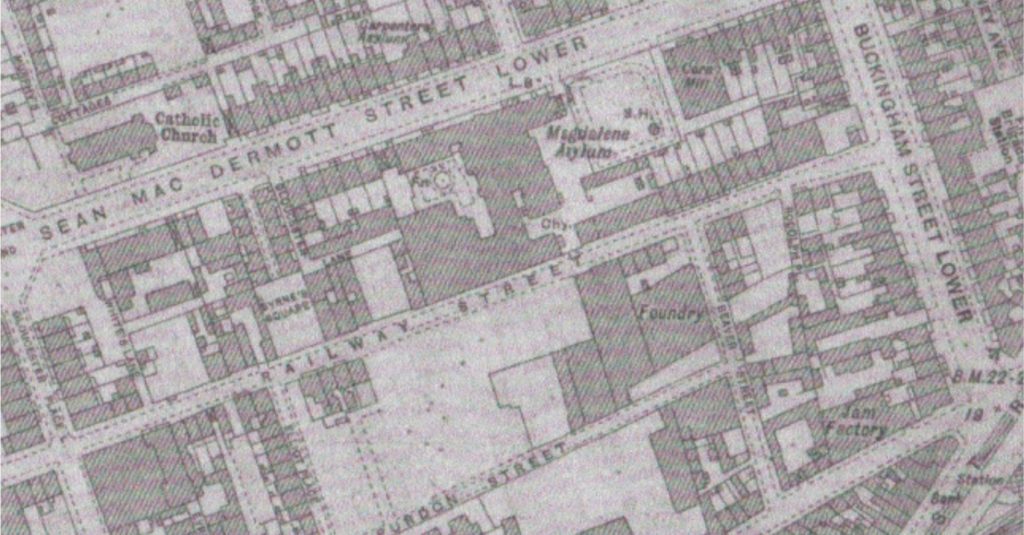

- In 1821, a refuge was established at Mecklenburg Street (later re-named Railway Street, at the rear of Gloucester Street) by a layperson (Mrs Brigid Burke) for ‘troubled and homeless’ women. Over time, a four-member lay Committee became responsible for the institution and a Matron was employed to operate it. In or about 1860, the Committee purchased additional land to include a site on Gloucester Street (later re-named Sean McDermott Street).

- In 1873, Cardinal Cullen requested the Sisters of Mercy to take over the operation of the institution, then known as the Magdalen Retreat, which they did until late 1886. At that point, and with the approval of Archbishop Walsh, the Sisters of Mercy requested the Congregation of Our Lady of Charity to take over operation of the institution. The Sisters of Our Lady of Charity did so and became responsible for the institution in February 1887.

- There were no other institutions on site, other than the laundry, living quarters for the women who worked there, and the Convent.

- The capacity of the Magdalen Laundry at Sean McDermott Street was 150. Occupancy varied over time- it was 120 in 1922, 130 in 1932, 135 in 1942 and 140 in 1952. The Laundry ceased operations in 1996.

The Appendix to the 2013 Inter-departmental Committee Report provides several Ordinance Survey maps of the site, from 1907/08, 1936 and 1990/91.

History of the Area Surrounding the Sean McDermott Street Magdalene Institution

The 2-acre former Magdalene Laundry site at Sean McDermott Street is an area bounded by Talbot Street, Amiens Street, Gardiner Street and Seán McDermott Street (formerly Gloucester Street). This area of less than one square mile was known throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century as The Monto (as Montgomery Street was its central thoroughfare) and it was one of the world’s largest red light areas, due to the fact that Dublin was one of the most heavily garrisoned cities of the British Empire.

The Monto was also fondly known as ‘the Village’ to many of its regular denizens who liked to drink in the neighbourhood pubs and James Joyce memorialised the lively, bawdy, demi-monde community of Monto as ‘Nighttown’ in the fifteenth chapter (“Circe”) in Ulysses. ‘The Village’ was central to the streets and docks where most of the early twentieth century Republican (Feminist & Socialist) Revolutionaries lived and this was the neighbourhood where Ireland’s ‘Cultural Revival’ was made manifest: in the theatre of the Trade Union building Liberty Hall, in the Abbey Theatre founded by William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory and now known as the Irish National Theatre and in the feminist, socialist and Irish cultural publications produced in the presses of that area.

It was in the surrounding tenements that Peadar Kearney wrote Ireland’s national anthem and if the landmarks of Monto could reveal their secrets, they would illuminate our understanding of our revolutionary past as it was also here that many a note was passed, in local pubs such as Phil Shanahan’s, or Cleary’s, which acted as rendezvous points for Irish Republicans during the revolutionary period.

Current Environment of the Site

There still exists a thriving community in Monto, full of characters adding ever more layers to the cultural tapestry of the area.

Still living in close proximity to the Magdalene Laundry site at Sean McDermott Street is playwright and actor, Thommas Kane Byrne, who recently completed his “Monto Trilogy” of plays which explored the heart and humour of modern inner city life.

If you take a walk through Monto today, you’ll see pictures of local hero and world champion boxer Kelly Harrington adorning the streets where she still lives today. You’ll probably bump into Hollywood actor Barry Keoghan visiting his family and undoubtedly, you’ll spot local folklorist Terry Fagan working hard to preserve and pass on the proud history of the community to the younger generations.

The architectural history of the buildings close to the Magdalene Laundry site is equally spectacular, and their decayed stated equally lamentable. The long promised regeneration of the Rutland Street school building seems closer than ever, but still, this building – which could act as the centre of a cultural revival in the area – remains vacant and lifeless. The many vital projects of the Lourdes Youth & Community Services, such as the crèche and adult education programmes which for decades kept a presence in the ‘Red Brick Slaughter House’, were removed in 2019 on the promise that they could return once the building was restored by Dublin City Council. As we note on our Home Page, is crucial that any redevelopment of the Sean McDermot Street laundry site is carried out alongside the restoration of Rutland Street School.

Just a stone’s throw from the Sean McDermott Street Magdalene Laundry site is the now derelict Aldborough House, one of the finest examples of eighteenth century Georgian architecture that remains standing. A building upon which Leinster House was modelled, Aldborough House stands as a cautionary tale regarding what can occur to buildings of historical importance that are relinquished from state ownership. It has for almost three decades been passed from owner to owner, without finding any purpose or investment in its care.

What is distinctive about the area that surrounds the Laundry is just how many of its locals continue to work to the aid of their community. Locals work in community youth groups such as The Belvedere Youth club, set up to provide a place to the ‘newsboys’ of decades ago, while childcare providers such as the LYCS and the Community After Schools Project are essential supports to the community and locally run.

Organisations such as ICON, the Crinan and the SWAN youth services have provided community leadership for many years in response to the drugs epidemic that engulfed Dublin from the early eighties. These groups remain present in the community today and are essential to the fabric of the area.

The iconic Liberty Hall and the world famous Abbey are less than ten minutes’ walk from the Sean McDermott Street Magdalene Laundry site. Within five minutes’ walk from the site lie: the Custom House on the River Liffey; the Irish Financial Services (IFSC) district; Ireland’s largest railway station and largest bus station, as well as the capital’s main street, O’Connell Street. The proximity to such vibrancy underscores the eerie quietness of the site to be developed and brings into sharp relief how the surrounding streets of the former Monto/Village seem pock-marked with social deprivation: many commercial units remain empty at the street level in the former Montgomery St (now called James Joyce Street). A rare burst of life in the area can be seen in the flurries of arrival and departure of the multi-ethnic 160 young children who attend the Rutland National School, which is officially ranked as a school catering to the most economically vulnerable.

‘Gloucester Street Magdalene Laundry’ by Cian Brennan, Gary Gannon & Stephen Maguire, 2017.